Thinking about

a betterdammerung

I have only known anything about Wagner's Ring cycle (beyond the titles, the Looney Tunes version of the Ride of the Valkyries, and the ambient cultural information available about the basic plot) for about 48 fever-riddled hours, during which time I have watched all four operas in the form of a YouTube upload of a 1980 recording, and read Kate Wagner's excellent Walsung essays as a sort of wise elder guide on this journey. (Götter bless the uploader, the translators, and Kate Wagner). I feel, then, definitely qualified to have an opinion about staging this piece of media that people spend whole careers unpacking. Here are the director's notes for a theoretical universe in which I have unlimited resources to produce what I can confidently assume would be the undisputed perfect canonical version

THERE SHOULD BE MORE LIVE ANIMALS

The Valkyries should ride horses as often as possible. Actually, Freia should also have live rams pulling her chariot onto the stage to meet Wotan in Die Walkure too. If this version of Die Walkure has to be staged on the grounds of a ren faire in order to handle that much livestock then so be it. The Chereau/Boulez-directed production I watched (hereafter just C/B) used a live bird in Siegfried and that was rad even/especially when Siegfried sort of awkwardly tossed a handful of live flapping bird out of its cage. More of this for sure

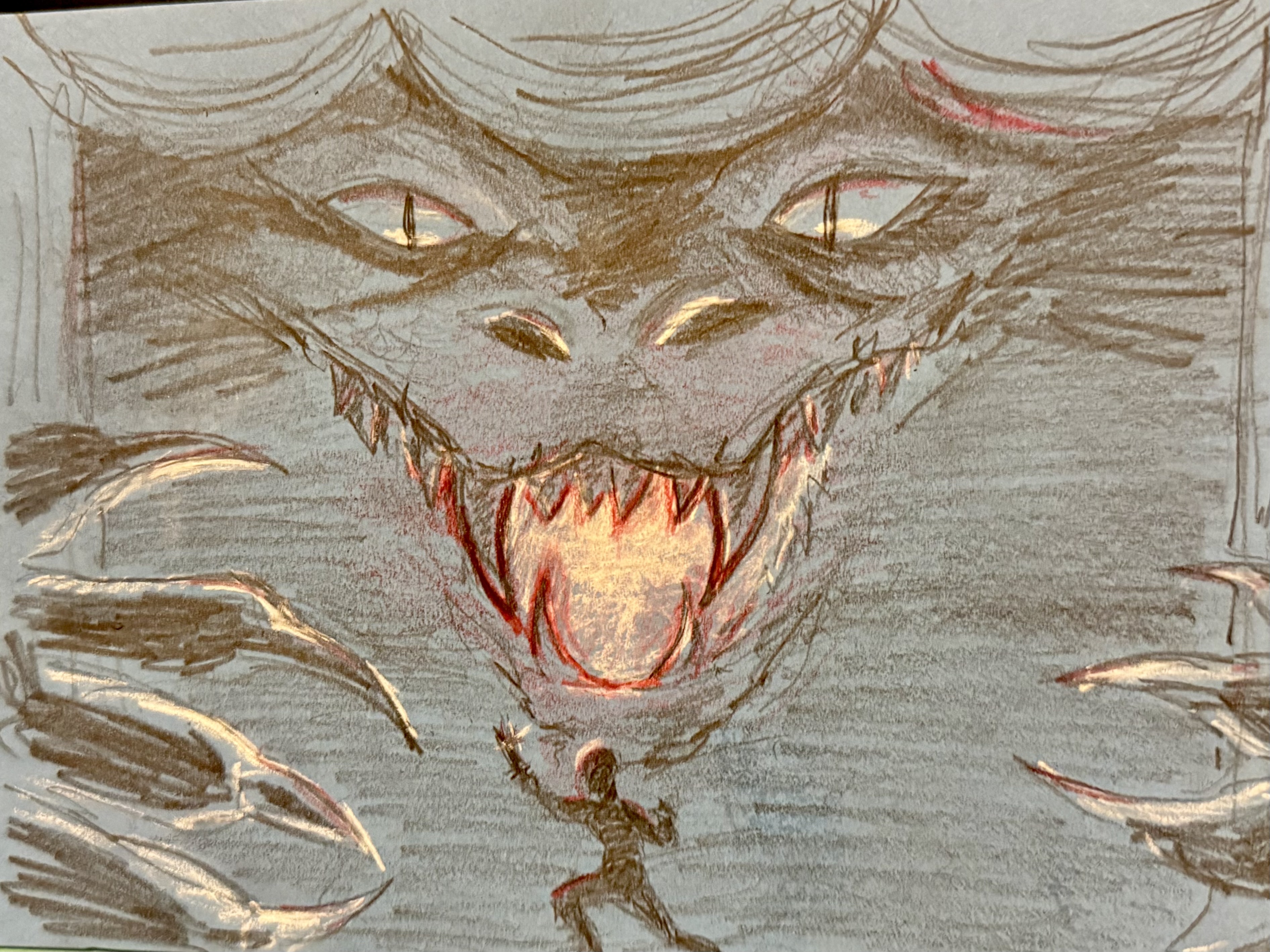

THE DRAGON SHOULD BE BIGGER

The giants in C/B are like 1.5-scale regular dudes, which is great actually, and they have unsettling forehead prosthetics and doll arms which gives them an uncanny valley effect. I would keep this approach I think. The dragon left me cold, however, even though I admired the ambition and the cart-based mobility.

I want RPG-boss scale here; a backdrop-sized face should seethe smoke from the darkness of the rear stage until it opens to reveal its own light source, a red flame glowing in the massive throat and illuminating rows of man-sized teeth. Curling claws like great branches should slide in on each side behind the forest scenery and nearly enclose our brave hero. The face can rise beyond the limits of the stage aperture to reveal what seem like miles of throat until the scaled breast is seen, and Siegfried pierces the (perhaps ember-red) heart. Then the whole dragon installation will collapse into a great pile of fabric, the light will go out behind it, and the giant will lay beneath this crumpled mass until invisible backstage hands pull it off to the side to reveal Fafner's original form.

SIEGFRIED SHOULD CLEARLY BE THIRTEEN YEARS OLD

Siegfried is a weird feral man-child and I think this is a shonen anime Freudian nightmare about puberty coming of age story and I think to emphasize that and to make the audience more uncomfortable on purpose I would cast an actual child-but-almost-teen to be our guy. He's supposed to be realizing his differentiation from his known parent figure (Mime), yet still yearning for some connection to his birth mother, and then to finally feel fear at losing his virginity, to hesitate at the prospect of crossing the threshold into sexual maturity. He's almost shockingly immature and uncomfortable to watch as an adult going through some of this? Obviously watching a thirteen year old do the same would be weird from the other direction but it's closer to my interpretation of where the dissonance should be felt in the story. The Brunnhilde forced-marriage via probably-fake-"destiny" deal is already sickeningly coercive, in other words, that's The Theme; in fact everything that happens to Siegfried is him getting pushed around on a chessboard by the gods, so it would be an extra layer of emphasis on his agency being co-opted by the real adults. Even as he sees himself a man, a hero, because, uh, a bird told him he's destined to rule the world, his imagination ends at doing exactly what he's told to do. And like we already got the incest to deal with right

If there aren't any stunningly gifted opera-singing thirteen year olds who would make the cut we could even have an adult sing offstage to make the whole thing weirder and worse.

BRUNNHILDE SHOULD ALSO BE A TEENAGER BUT WE SOMEHOW DON'T REALIZE HER IMMATURITY UNTIL LATER

For similar reasons related to Brunnhilde's enmeshment with Wotan I think it would be interesting to cast her quite young but hide her face in her introductory scene. Wotan first seems to address her as a military subordinate (albeit clearly one who speaks freely with him) so she could retain her helm until, ideally, her pivotal moment of decision in offering to shield the Walsungs, at which point it would be clear to us that this is the first moment of her true adulthood, the capacity to exercise her own will.

THE COSTUMES SHOULD BE DOING MORE VISUAL INTERPRETATION

I really aesthetically like the all-over-the-fashion-timeline + fantasy blend that C/B went for (with the notable exception of the ill-fitting Brunnhilde helm). Wotan's suits are great, Freia's dresses are awesome, Erda's ... fabric-pile is perfect, Mime's trapper-coat is appropriate, the Gatsbyesque modernity of the Gibichungs hits the right note. The C/B production gets halfway to what I want which is to use costuming choices to make certain character traits more obvious, e.g. Freia's old-fashioned nature, Wotan's progress into modernity, Siegfried's storybook-hero idealism, Erda's elementality.

The scope of the story is the apocalypse at the end of time from the Gods' perspective; I would love to see an extension/exaggeration of this same costuming approach to expand the visual/fashion timeline palette. I want to see Wotan progress from the 900s to the 1980s, with Freia stuck in the Renaissance, Erda half-rock in her awakening scene, Siegfried dressing himself like a cardboard 60s space age hero. This would also give us an opportunity to use a surreal blend of every Ring adaptation/influence to informing each character visually. Also Wotan could go through a series of more and more awesome eye patches.

I AM A HUGE FAN OF LOGE LOOKING AND BEHAVING EXACTLY LIKE RIFF-RAFF SO THAT STAYS, THOUGH

Please call Richard O'Brien and ask if they'll be in my play

SPEAKING OF PROPS, THE RING SHOULD BE MORE VISUALLY NOTICEABLE

So this whole thirteen hour musical and visual spectacle is about a ring, which is a very tiny object, so how do we solve that and make it noteworthy when it's actually physically in the scene? C/B decided to make the ring kind of large and an obvious visual parallel to the bright, craggy Rheingold, which I like! Though I think maybe I would do a more svelte ring since the most familiar cultural artifact is now Tolkien's ring and we all know that looks like a simple band; I would perhaps do a lighted "gold" ring so that it's difficult to not notice it, or ALWAYS light it with a spotlight when it's on stage.

a wretched hive of scum and villainy

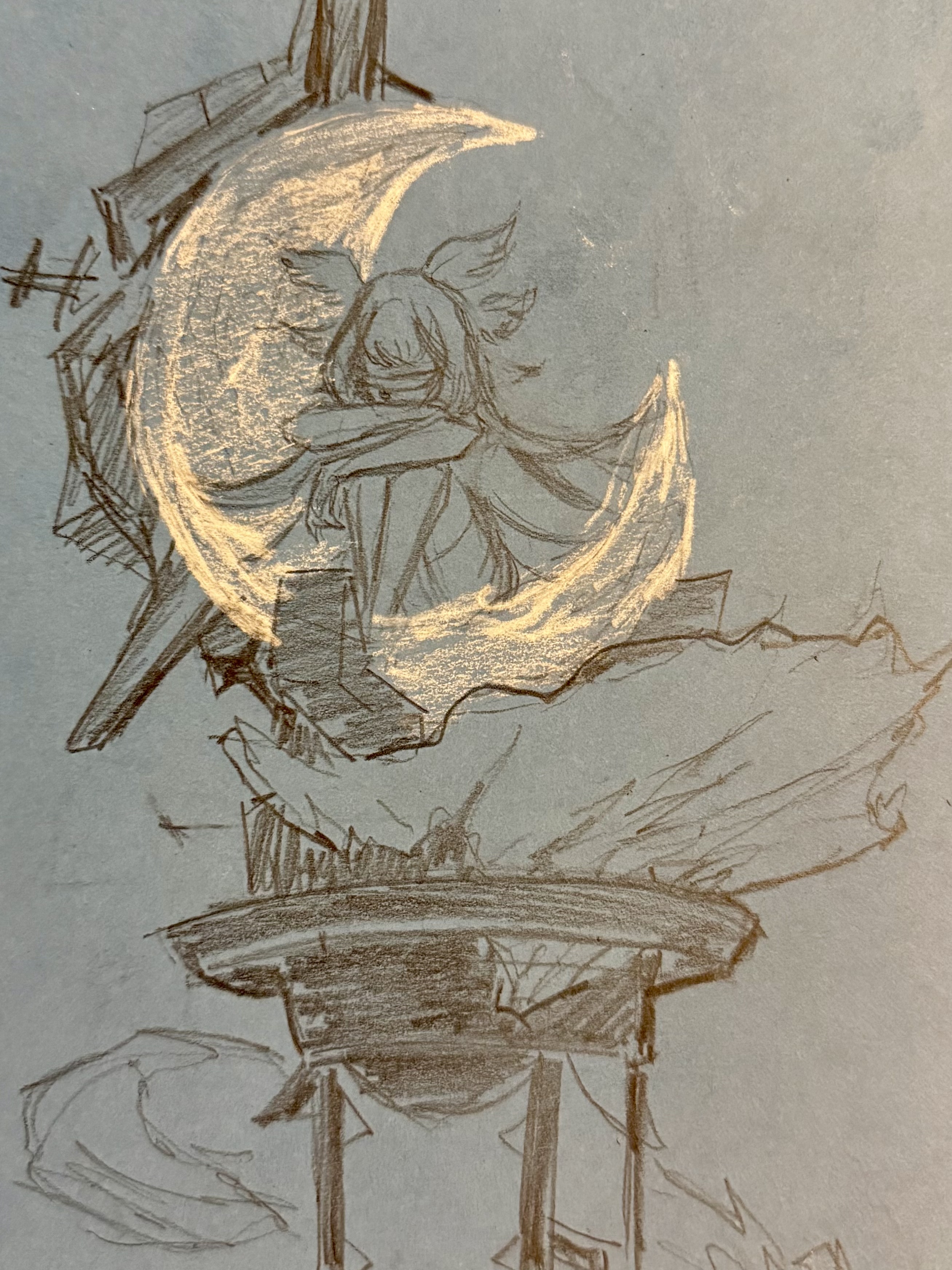

I like to say that Genshin Impact is a several-hundred hour opera to me, due to my investment in the musical storytelling, so this is a segue: Speaking of opera!

I was so excited about the launch of the newest area of Teyvat being released that I took a day off just to play that. This enterprise was somewhat undermined by having had COVID the week prior and thus not really being in need of an entire day to stare at a screen but I took it anyway. I love the new area, I'm sure partly because I had prepared myself so intently to enjoy the new area, in a way I haven't for a couple of major versions which correspond to real-life years. Generally I hope that art I spend a lot of time consuming will stick with me for more than a couple of days past the time I consume it, and Genshin has reliably provided me with experiences that I've kept thinking about. (Being no fan of a huge corporate cinematic universe, I have some ambivalence about being so entrenched in one game for so long but media consumption does not primarily define my ethics.)

I'm most compelled in this new section of plot by the convincingly varied personal motivations of the characters in Nod-Krai; though a nominal holding of the vast winter empire Snezhnaya, Nod-Krai is a historically diverse and culturally independent area which mostly holds no particular reverence for that empire, nor any particularly acute separatist fervor. We meet a handful of people from the various factions of Nod-Krai: a priestess of a shrinking and struggling ethno-religious group, a member of a citizens' militia which keeps the walking dead at bay, a genius child engineer who makes marvels of the thriving scrap trade passing through Nod-Krai, several brands of opportunistic expats here to enjoy relative lawlessness. I'm enthralled simply by the vibes here, the sense of living on the edge of the civilized world. NPCs laud their cherished freedom, the only universal Nod-Krai value, but the landscape is full of Nod-Krai cultural buildings and statues refashioned with the imagery of the Fatui, world-famous military and intelligence engine of Snezhnaya. The visual landscape bears a lot of the story, throughout the game, giving a palpable sense of being situated on the top layer of a geologic substrate made up of lost ages and cultures; in Nod-Krai, we watch the next layer being laid in real time. It's kind of sad and intense even just to wander around here, if you're tuning in to what the landscape is communicating.

iceberg ahead

Watching Code Geass in 2025 is a bizarre experience because I think in the Obama era when I still believed politicians were, if sometimes/often morally bankrupt, at least people with complex ideas, I would’ve rolled my eyes harder at the sometimes half-baked thought experiments represented by the main plot of this anime, but now I’m finding myself wondering if some high schooler could make an AI deepfake terrorist with no face trick Trump into deporting all trans people to a man made iceberg governed only by international maritime law.

If nothing else I think this show has something interesting to say about how even being very close to the engines of power does not in fact confer control over events. It has a sometimes frustratingly simplified politics -- a struggle against a big empire with an evil might-makes-right dude at the top, a scrappy noble band of subjugated people in their stolen robots trying to wrest independence, plus some surface-level moping on the part of the protagonist, leader of said rebels, about having to make politically calculated decisions that hurt people. The plot kind of saves him from a more thoroughly explored and interesting version of this, which makes it unsatisfying: the worst atrocities are contrived to be not his fault, and he spends a lot of time worrying about these at the expense of lower-body-count decisions for which he actually is morally culpable.

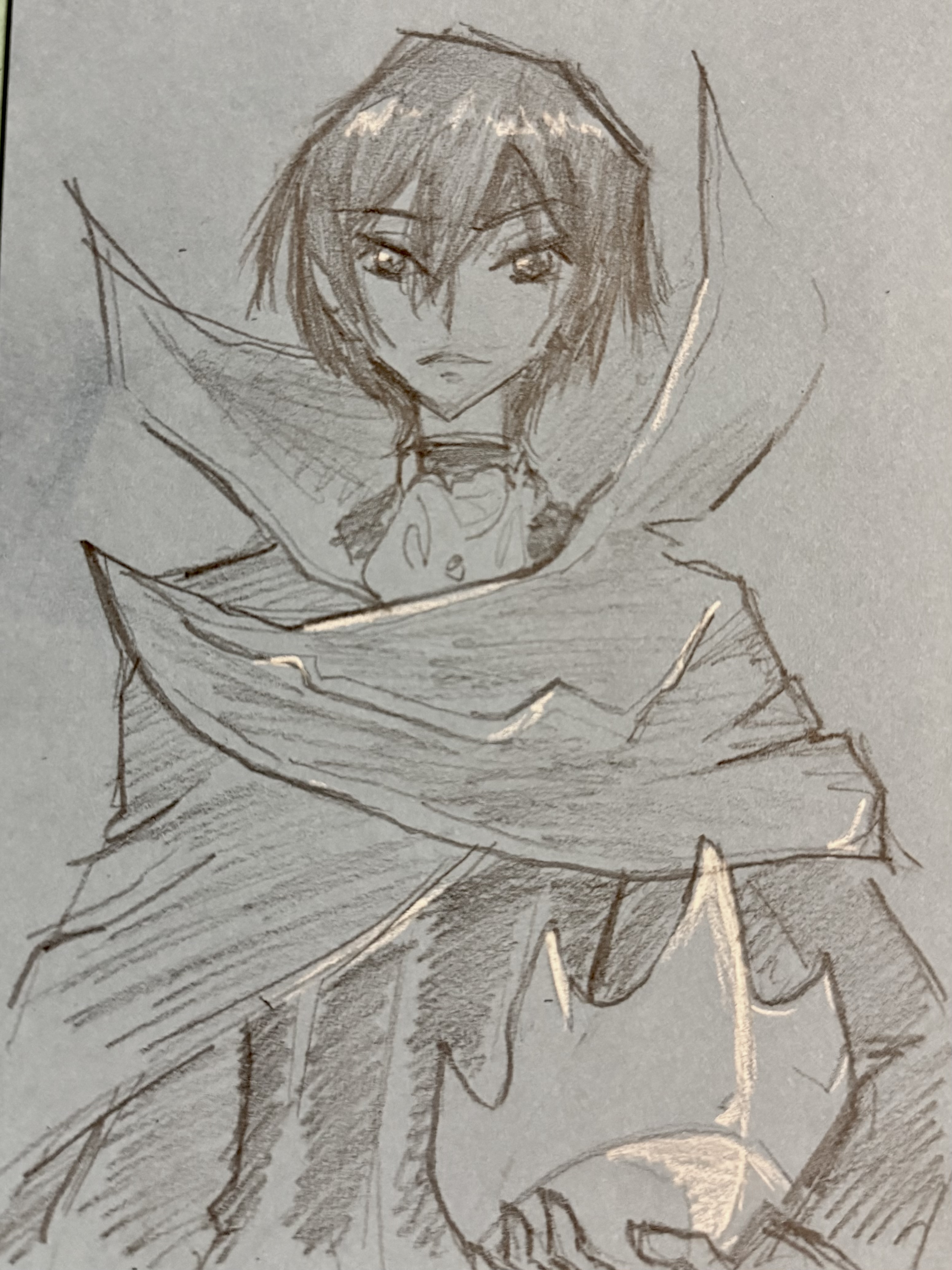

Still, I admire the complexity presented by the identity of the protagonist; Lelouch is not a member of the subjugated "Elevens" (the Japanese people, stripped of their cultural identity down to erasing its very name, in an effort to assimilate them to the world-spanning empire of Britannia), but a Britannian, in fact a son of the emperor, a prince something like 20th in line for the throne. He is one of some ridiculous number of the emperor's children which I think is a nice neat way to demonstrate the Britannian emperor's ethnic natalist politics. I think they drew like 14 frames of this guy total but he's got a really palpable presence and a clear politics that resonates convincingly through the lower levels of the government acting in his name, which is what the plot mostly has contact with.

So in episode 1 Lelouch, exiled prince of Britannia, gains bullshit powers that I refuse to discuss because they would not matter to the plot except to conveniently excuse Lelouch from ethical dilemmas as mentioned above, and they are thus probably the worst part of the show. This arbitrary inciting event inspires him to invent the persona of Zero, masked leader of the Black Knights, a rebel group intent on winning back Japan's independence and identity. The rebellion, though, is merely a front for Lelouch's personal vendetta against the Emperor, for the failure to investigate the mysterious death of Lelouch's mother. Mother Marianne's ghost hangs over the proceedings like the King of Denmark, and Lelouch has some of Hamlet's mercurial madness and willingness to play a role to get what he wants, ultimately at the expense of the solidity of his real identity. Shades of Dark Knight-esque "are you the man or the mask" going on here too, as the plot zooms in and out vertiginously between slice of life shenanigans at Lelouch's private Britannian school and masterminding paramilitary operations ("I have a school festival and a coup d'etat to run!"). He cheerfully pretends to have a crippling gambling addiction in order to explain away his absences from school which is one of many characterization choices that seem initially insane but then settle into a certain kind of madcap coherence.

Halfway through season 2, Lelouch Batman-Hamlet is finally perhaps starting to care about his own stated mission to win Japanese independence, having been confronted by the disconnect between his primary motivations and his growing sense of obligation to the people he's inspired to take up the (for him, at first, false) banner of rebellion. I thought at the end of the first season that maybe the show had given us a sort of straightforward bait and switch with an ultimately inexcusably cruel and selfish protagonist, but his arc instead bends toward actual justice rather than merely wearing its mask. For now, anyway; one thing I admire about the show is a sense of grounded unpredictability; the introduction of new characters bringing huge plot curveballs in another show might feel pretty cheap, but here it feels like satisfying minor surprise, since the world is established to be politically complex enough that we expect the intrusion of new agents of fate all the time to steer world events.

And it reinforces the most interesting feature of the show's political themes: politics framed as an emergent property of personal relationships and motivations and philosophies. Zero is in fact entirely a political fiction, literally masking a personal grudge. Zero is politically and militarily adept in the same way that Lelouch is an expert chess player, but both identities are often surprised and thwarted by the mystery of other characters' motivations, which turns out to be the more important part of politicking. Piloting the stolen robot army with near-omniscience is great and all, but that is, it turns out, not the whole chessboard. The iceberg move jokingly referenced above was a sort of stupid but also thematically really brilliant bit of plot: Zero acquiesces to a compromised "Japan autonomous zone" that remains under the control of the Britannian empire but is allowed some concessions to maintain their cultural identity, in exchange for Zero's exile (a move decided by Britannia as the best option for punishing him as a terrorist but not making him a martyr for further rebellion). During the course of negotiation with the Britannian delegation, he is asked "Are you the same Zero as before, or someone new?" and he asserts "It's not what's inside which determines who Zero is. It's the actions which measure the man." In the same conversation he asks "What does it mean to be Japanese? To be a citizen of a country? Language? Territory? Blood Ties?" A knight answers "Heart" and Zero agrees: "I think the very same. In short, so long as they have the roots of their culture in their hearts, then they are Japanese no matter where they live! Japan is not a place; it's a people." Accepting these two seemingly unrelated philosophical premises turns out to be the basis of legally exiling a million Japanese citizens disguised as Zero and acting as rebels, effectively winning extradition for all his adherents from the Britannian Empire and then re-founding Japan on a manmade iceberg ship. Zero also, crucially, hangs this plan's success on accurately understanding another person's core motivations; the plan only works because he knows one of the Britannian knights, and he counts on his dedication to peace in order to execute the culminating scene of the plan. Zero did certainly need to win the robot battles to get in the room with the Britannians, but he also needed to win the word game of political philosophy, and to know and even in a certain sense trust his enemy. Most animes with robots in them, and in fact most media about scrappy rebels, would definitely stop at the battle won by the underdogs, and I admire the ambition of Code Geass to explore a little further even in a wacky manmade-iceberg-based direction.

engines of power

A more developed version of this, uh, "essay" would maybe examine the intersections of literal and metaphorical political machines -- the Fatui and the Britannians have won cultural hegemony with robotic firepower1, and they justify their conquest with a narrative of the march of progress. Alberich2 the dwarf subjugates the Nibelungs with the power of the ring, a forged, artificial technology that marks the end of the era of gods. These stories look at different moments in the technology-mediated hegemony: the looming threat in Genshin's Nod-Krai, the fall in the Ring Cycle, the consequences of established empire in Code Geass. It could be something like an operatic meta-cycle of techno-empires if only Code Geass had good music. (If there's a stage musical for Hunter x Hunter and Sk8 the Infinity maybe there is a Code Geass musical...)

I write this from my own position in the timeline of real life techno-hegemony and so I've been somewhat affected by these stories as I interpret them. I suspect Nod-Krai is primarily meant as a carefully-not-exactly-specific analogy to culturally independent zones of the world (most notably the Baltic states) rather than a general metaphor for living in an age characterized by large cultural powers eroding smaller ones, but this theme/feeling is, for me, less nationalist and more resonant with the absorption of every subculture disappearing into the mainstream, every creative outlet bought up by the same five companies that already own almost everything, even every word shared on the internet being digested by capitalist AI behemoths. The machines are in the midst of winning, the sun never sets on Meta's empire.

Which is all a little depressing, to be sure, and I don't think any of these stories really offer a convincing alternate ending to the machine hegemony. Brunnhilde burns herself on the pyre of the old world and we don't really know what happens after that but everything is constantly getting worse for everyone in these operas so it's definitely not looking up. Nod-Krai must resist intrusion or be overtaken, by the undead or by the imperial military. The old and the new always intrude on the present. What would it mean to hold out forever? One of Genshin's recurring themes is erosion and corruption, magical and cultural and personal: how long can a culture hold onto itself without rotting from the inside? Is that even desirable, or is that its own kind of undeath? It makes naive sense that progress might be the antidote to decay, but progress is an awfully suspect framework in the context of empire. The future sold to us by those who already have the power to demand any sacrifice in exchange.

Zero, well past the climax of empire's triumph, rouses his followers: "Don't be naive. If you think that someday someone will come and free Japan, then that 'someday' will never come. If Japan is ever going to be freed, then it is going to be done by us, and now." Much to be said about the tactics of propaganda he openly employs, about the symbolism of relying on stolen robots, about the necessity to recruit a Britannian propagandist and a roboticist from another colony to further the rebels' aims, about using hostages and lies and feints. Zero plays to win, not for his tactics to be admired. Optimism and naivety are decoupled, here: he does not call the dream of independence naive, but he indicts the idleness of a dream without action, a dream conveniently deferred to the future. He assigns responsibility and urgency: "It is going to be done by us, and now."3

And it is thus with optimism but not naivety that he announces to the empire, "Those of you with power: fear us. Those of you without it: rally behind us." Down with the robot empire!

[1]: This doesn't fit anywhere but Code Geass calls its technocrat war engines "Knightmares," which is pretty great ↑

[2]: The name Alberich is borrowed for the founder of Genshin's Abyss Order, who (similarly but more explicitly) seeks to overturn the rule of the gods by the forbidden use of power, a twisted form of the energy latent in the landscape itself. (I think. This area of Genshin lore is not... yet... super clear to me...) ↑

[3]: Against Zero's direct advice, this specific line/scene makes me yearn for a real-life rebel leader of some kind who can speak like this, but the whole point is not to yearn for someone else to enact rebellion for you. Unfortunate! ↑